September 22, 2016 Mikayla Mace

By MIKAYLA MACE

Arizona Sonora News Service

The sun sets in Tucson; street lights blink on; storefronts glow. From downtown, you can see a handful of stars, and quite a bit more if you are in other areas.

But where is the Milky Way in that night sky? Despite Tucson having long been known as the home of the International Dark Sky Association (IDA) and the astronomy capital of the world, the galaxy has largely faded from view in the city where the global dark sky movement began.

We talk a good game of dark skies, but does Tucson really play that game? Are we losing ground, so to speak, in the quest for dark skies with less visual pollution from artificial light?

“Tucson has never approached us about being considered a Dark Sky Community,” said John Barentine, program manager of the dark sky organization, which was founded in Tucson in 1988. Over the years, communities in both Flagstaff and Sedona have applied and earned the distinction of a Dark Sky Community, of which the dark sky association currently lists 12 around the world. “I like to tell people that New York City could be a Dark Sky Community if they wanted to,” he said. Cities don’t have to start with dark skies, but cities do need to actively reduce and control light pollution.

The view from a 10 minute hike from the Mount Lemmon Sky Center on Mount Lemmon in Tucson, Ariz. on Friday, Sept. 9, 2016. The high pressure sodium lights that line Tucson streets cause the golden glow over the city that astronomers have to work around. Mikayla Mace / Arizona Sonora New Service

It would seem as if Tucson would want to. Tucson is known for its long and proud embrace of academic and amateur astronomy. The Tucson Amateur Astronomy Association regularly host star parties in and around the city. Astrophotographers, who snap nighttime images of the Milky Way and other celestial objects, such as Sean Parker, hold workshops in Tucson because of the legacy of dark skies.

It’s true, for a city its size, Tucson has skies that still are fairly dark, especially out around city limits.

On the other hand, many Tucsonans are among the 80 percent of North Americans who say they have never seen the Milky Way, according to a recent study (click here for the paper and images) by the Light Pollution and Science and Technology Institute in Thiene, Italy. The study combined satellite data and sky brightness measurements to create a world atlas of sky brightness.

Coincidentally, 80 percent of the U.S. population live in cities, according to the U.S. Census.

So the debate continues: Are Tucson’s skies dark enough? And what is Tucson doing to stay in the game?

Let’s get down to business.

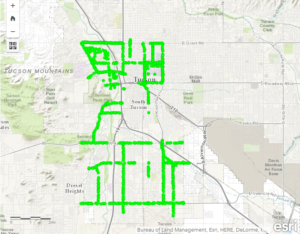

The city is retrofitting old streetlights with new light emitting diodes (LEDs) which were purchased from American Electric Lighting. As of mid-September, the city has installed about 3,400, and continues to do so at a rate of 1,400 a month. Throughout the decision-making process, Tucson consulted with IDA board member and lighting expert, Chris Monrad of Monrad Engineering, Inc. These lights will save the city $180,000 a month in electricity costs, reduce demand on fossil fuels and not add any additional visible light over Tucson, according to Jessie Sanders LED Project Manager for the City of Tucson. The city also expects approximately a $2 million rebate from TEP (Tucson Electric Power), and to have the $16.5 million project cost paid for by energy savings within 10 years.

All LED streetlights are initially dimmed to 90 percent of maximum brightness. Most LED lights are dimmed to 60 percent brightness at midnight. For the University, downtown and Fourth Avenue areas, they are dimmed at 3 a.m. Intersection lighting always stays constant. Most street lights are shielded (including the new LEDs) so no light is projected directly at the sky.

High-pressure sodium street lights accounted for 90 percent of Tucson’s street lighting and have a color temperature of 2700 Kelvin (K). Color temperature is used to characterize the quality of light where higher numbers are considered “cool,” and smaller numbers “warm.” The sun’s light is 5800K and shines white.

High pressure sodium lights emit mostly yellow light but also do contain small amouts of blue light. The new LED lights glow at 3000K, a similar quality to the high pressure sodium lights, but which emit an even broader spectrum, providing a wider color range. So while the temperature is similar to the old sodium lights, these lights also emit blue light.

These LEDs do give off more blue light when you compare it to a high pressure sodium light of the same brightness, according to Monrad. “However, we are not replacing all HPS (high pressure sodium) with LED on a lumen for lumen basis,” meaning equal brightness. The City of Tucson is actually dimming the LEDs (not including the previously mentioned dimming strategies) so that overall, they emit less blue light than the old high pressure sodium.

This reporter used a spectrometer to record her own spectra of the new lights and found that there was little blue light, which looked at least comparable to the high pressure sodium, emitted from the LEDs.

What does this mean for our skies?

Blue light at night disrupts the human sleep cycle, and adversely affects health, according to the IDA and American Medical Association.

The city took this into account and is following the recommended guidelines of the IDA, the federal high administration safety guidelines and the American Medical Association, Sanders said, by capping light temperature at 3000K and dimming at certain times of day. Tucson has also installed the LED lights to fit the existing outdoor lighting ordinances adopted by the both the city of Tucson and Pima county even though when the codes were passed, LED technology was not specifically addressed in the ordinance. The City estimates that the LED lights will reduce visual sky glow by 20 percent, according to Sanders.

Something to remember though is that blue light scatters more than yellow light for the same reason that our skies are blue, according to Richard Green, assistant director of government relations for Steward Observatory, and director of Kitt Peak Observatory from 1997 to 2005.

But if too much blue light builds up, there goes the view of the stars.

In a region where astronomy is very important, astronomer’s views count of course.

For astronomers, blue light won’t disrupt observatories around town because it will have dissipated before reaching their lenses, Green said.

Kitt Peak, located about 7,000 feet above sea level and about 50 miles southwest of Tucson, and the Catalina Sky Survey, perched at about 9,100 feet at the summit of Mt. Lemmon, are both involved in government-financed location of near-Earth-objects—asteroids headed for Earth. So a clear, dark sky is very important to the mission of global security.

Kitt Peak, located about 7,000 feet above sea level and about 50 miles southwest of Tucson, and the Catalina Sky Survey, perched at about 9,100 feet at the summit of Mt. Lemmon, are both involved in government-financed location of near-Earth-objects—asteroids headed for Earth. So a clear, dark sky is very important to the mission of global security.

For the Catalina Sky Survey, Tucson’s increasing light pollution is always discussed when plans for new telescopes arise, according to Eric Christensen, director of the Catalina Sky Survey. Pollution from artificial light is one thing, but it can be mitigated. Natural celestial light, of course, is another thing. Around the time of the full moon, for example, operations shut down for up to five days.

What Christensen has noticed the most is light pollution from Oro Valley. He attributes light pollution not to the quality of light, or lack of ordinance compliance, but most of all to population growth. Dr. Robert (Bob) McMillan, who has led the Spacewatch Project on Kitt Peak since 1980 agrees that population growth is the greatest impediment, after moonlight.

Barentine worries that as the population, and ultimately, light pollution in Tucson grows, Tucson will lose more of its astronomy standing and industry revenue to places such as Chile and Hawaii, which are the new hot spots in the age of extremely large telescopes perched at extremely high altitudes.

But currently, it’s politically very hard to add more telescopes in Hawaii, and Chile observes the southern hemisphere sky, Christensen said, adding “southern Arizona still has the highest concentration of research telescopes in the continental U.S.”

“I’d say Mt. Lemmon is still in the upswing,” Christensen said. The program is still growing; projects continue to be funded.

McMillan said, “Kitt Peak still has more to contribute.”

In fact, according to Green, a 3-D galaxy mapping project called DESI (Dark Energy Spectroscopy Instrument), funded by the Department of Energy, has begun construction and will be installed on Kitt Peak, with observations beginning in 2019. A new project using the NOAO (WIYN) telescope on Kitt Peak, in partnership with other telescopes around the country, will confirm and characterize exoplanet discoveries, according to NASA.

Is Tucson’s future bright or dim?

The IDA warns that the availability of cheaper light means inviting the installation of additional lights, a phenomenon called Jevon’s paradox. And as the population increase, so will the amount of artificial light.

And despite the effective outdoor lightning ordinances in place in Tucson and Pima County, small electronic signs are not included (giant electronic billboards are banned in southern Arizona, according to Green). Barentine sees this as a threat to dark skies. Tucson could look to Sierra Vista and Cochise County as a model for codes addressing outdoor electric signs, he said.

Astronomers are constantly aware that if population grows too much, or the ordinances aren’t followed and light pollution gets out of hand, that could be bad news for the telescopes in the immediate area, such as Mt. Lemmon observatories.

Astronomers aside, what about the rest of us in Tucson looking to see those stars at night? Are the new LEDs the answer? As Green said, “People have a universal right to starlight.”

Mikayla Mace has a bachelor’s in neuroscience, a minor in astronomy and is working on her master’s in journalism, so she can be a science writer and illustrator some day. Mikayla is from Tucson, Arizona and likes to read, paint, learn different instruments and play soccer in her free time.

Mikayla Mace has a bachelor’s in neuroscience, a minor in astronomy and is working on her master’s in journalism, so she can be a science writer and illustrator some day. Mikayla is from Tucson, Arizona and likes to read, paint, learn different instruments and play soccer in her free time.