NEW YORK (AP) — California and New York — where almost 1 in 5 Americans live — are on their way to raising their minimum wage to $15 an hour, and the activists who spearheaded those efforts are now setting their sights on other similarly liberal, Democratic-led states.

Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, Oregon, Rhode Island and Washington are among the states with active “Fight for $15” efforts, and even economic experts who oppose the increased rate see it gaining momentum.

“There is lots of pressure to do this,” said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a former Congressional Budget Office director who is now president of the conservative American Action Forum, which says big minimum-wage increases cost jobs.

The idea faces headwinds in more conservative and rural states in the South and the Midwest. But activists believe the movement is picking up steam, even if their two big victories so far were achieved in two highly receptive places: trend-setting, liberal, labor-friendly states with a high cost of living and yawning gaps between rich and poor, especially in New York City and Silicon Valley.

“In the beginning, it looked impossible,” said Alvin Major, a fast-food worker and leader of the Fight for $15 campaign. But now, “what happened in New York, in California, it’s going to spread around the country.”

Since the $15-an-hour movement planted roots with a 2012 New York City fast food workers strike, it has gained ground amid the broader debate over income inequality. Cities such as Seattle, Los Angeles and San Francisco have recently agreed to go to $15 in the coming years, and Oregon’s minimum wage is headed to $14.75 in Portland.

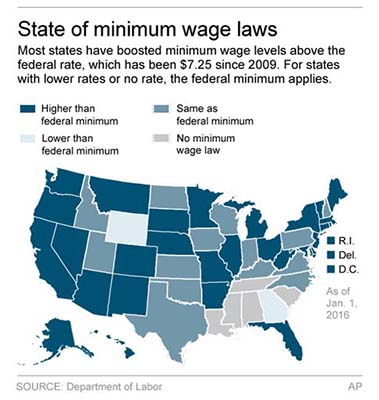

Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders has been pushing for a $15-an-hour standard nationally, while President Barack Obama has called more generally for raising the minimum wage. The federal minimum is currently $7.25; 29 states and Washington, D.C., have set theirs higher.

Sanders’ primary opponent and a former New York senator, Hillary Clinton, has supported raising the federal minimum wage to $12. Her campaign website says she also believes “we should go further than the federal minimum through state and local efforts, and by workers organizing and bargaining for higher wages, such as the Fight for 15…”

New York and California are now on track to have the highest. California Gov. Jerry Brown, a Democrat, is set Monday to sign a measure boosting the current $10 rate to $15 by 2022.

In New York, Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo and legislative leaders have agreed on a more complex plan. The $9 minimum would gradually rise to $15 in New York City by the end of 2018 and then in some prosperous suburbs by the end of 2021, but only to $12.50 in 2020 in the rest of the state, with further increases to $15 tied to inflation and other economic indicators. The measure headed to Cuomo’s desk after passing the Legislature on Friday.

New York’s graduated approach stemmed from negotiations with Republicans who worried such a sharp increase would devastate businesses, particularly in the more fragile economy outside the New York metropolitan area.

Similar dynamics may play out in other parts of the country. While $15 may seem reasonable in high-paying areas, “it’s a much harder lift in low-wage areas,” said Jared Bernstein, senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and former adviser to Vice President Joe Biden.

Also, California and New York have politically influential unions, strong community organizing activity and Democratic politicians eager to translate the movement into legislation.

“That’s not going to happen in some states, particularly in the South and maybe some of the Midwest,” said Peter Dreier, a politics professor at Occidental College.

Idaho lawmakers, for example, recently passed a measure barring local governments from raising the statewide minimum of $7.25, and Republicans in Arizona are trying to do the same.

The income gap has been widening in every state for at least 30 years but is particularly pronounced in states with large financial or information technology industries, according to economists Mark Price of the Keystone Research Center and Estelle Sommeiller of the Institute for Research in Economics and Social Sciences in France.

The top 1 percent of New York taxpayers, for instance, earned 40 times the average income of the state’s remaining 99 percent in 2011, according to research from University of California at Berkeley economist Emmanuel Saez. Nationally, the top 1 percent made 24 times that of everyone else; in California, the top earned 26 times more.

Economists have long debated the impact of raising the minimum wage, and some recent research has found that modest increases seldom cost many jobs. But the jumps to $15 are larger than those economists have tested in the past, and there are fears of widespread job losses in some places.

In New York City, Joseph Sferrazza worries that paying $15 will cost him his bakery, La Bella Ferrera. The rate is nearly double what he now pays his employees, mostly students working part time.

“The rent is so high, the profit margin is already so low, I don’t see how we can make it work,” he said. “You can only charge so much for a cookie.”

But $15 an hour would be a 50 percent raise for Maria Velez, 29, who makes $10 an hour working at a children’s program and helps support her parents and grandparents.

“This city is crazy expensive and only getting worse,” she said. If the boost took effect immediately, “it would make my life and my family’s life better — but in five years? I can’t say.”

___

Klepper reported from Albany. Associated Press writers Colleen Long in New York; Paul Wiseman and Christopher Rugaber in Washington; and Jonathan Cooper and Alison Noon in Sacramento, California, contributed to this report.

Copyright 2016 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

.jpg)