The largest farm on the Navajo Nation has been without water for more than a week after a pipeline break, endangering food crops worth millions of dollars and threatening jobs.

Most of the crops on the land managed by the Navajo Agricultural Products Industry near Farmington, New Mexico, were planted just before the concrete pipe failed, cutting off water to 72,000 acres of farmland. Officials have pegged June 11 as the date to have repairs completed, with water flowing through a canal system days later.

In the meantime, they’re holding out hope that the skies will stay cloudy and enough moisture will fall to sustain the plants in the desert.

“Hopefully with the small amount of rain we’ve gotten, that will help,” said LoRenzo Bates, a farmer who represents the region on the Navajo Nation Council. “At the end of the day, there will need to be some serious management decisions by all the growers as to whether or not to go with what’s still there or replant.”

The irrigation canal delivers water to the tribal farm from the San Juan River through Navajo Dam. The water that was in the canal when the 17-foot diameter pipe broke May 13 is being rationed among the crops grown by the tribal company and those who lease land.

A New Mexico State University research station is not taking water on its 250-acre plot nor is it planting anything new. Instead, the station is using the situation to study how plants respond to stress and the vulnerability of irrigation-dependent agriculture in the Southwest, said Kevin Lombard, superintendent of the school’s Agricultural Science Center in Farmington, New Mexico.

“It’s not a good time to be worrying about not having water,” he said. “It’s very stressful, very emotional.”

Contractors and the chief executive of NAPI, Wilton Charley, said they believe the crops that include alfalfa, corn, beans and pumpkins can weather three weeks with little to no water, but anything beyond that becomes risky.

The U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs is responsible for operating and maintenance of the irrigation system that was built decades ago by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, federal officials said. The Navajo Nation oversees all on-site activities on the farms. Crews have spent the past week excavating the 20-foot section of pipe and figuring out where a replacement could be manufactured, given its age of 44 years.

The expectation is that it could be fixed by June 11, but it would take a few days to refill the canal before crops could be watered from it, bureau spokeswoman Nedra Darling said. Darling did not have a cost estimate and didn’t immediately know the pipe’s last inspection date.

Hauling water to the farms or laying a pipe across the wash are not viable options because of the size of the farmland, Charley said.

Already, the tribal farm and contractors are making tough decisions to let some crops go dry, forgo additional planting and lay off workers.

John Hamby, whose family owns companies that grow pumpkins and popping corn on 5,100 acres of the tribal farm, cut half of the staff after the water break, leaving 15 workers. The number of people needed at harvest time swells to 600.

The 1,000 truckloads of pumpkins produced per year are destined for fundraising and the popped corn to the wholesale market. Hamby said popping corn is less important right now than the pumpkins, which haven’t sustained much damage but also don’t need a whole lot of water right now.

“If this would have happened in July, this would have been a disaster,” he said.

Mark Anderson, who heads Anderson Hay and Grain Co. Inc., said the company will expedite its first cut of alfalfa by a few days. From there, it goes to a compressing facility in Los Angeles and to domestic and export markets and to dairy farmers in the United States.

“So there’s plenty of jobs impacted and plenty of customers and marketplaces that expect hay,” he said. “If there wasn’t a fix in fairly short order, there could be a fairly big impact.”

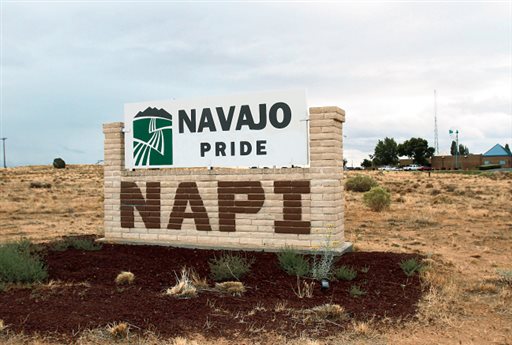

Some of the tribal farm’s inventory from last year still is being shipped to the market, Charley said. Alfalfa, pinto beans, potatoes and corn are sold under the Navajo Pride label. He said it’s too early to tell whether this year’s expectations for harvest will be met.

“Once we get a better handle of where we’re at, we’ll approach those discussions then,” he said.

Copyright 2016 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

.jpg)